The wager that never was

Misreading the Book of Job

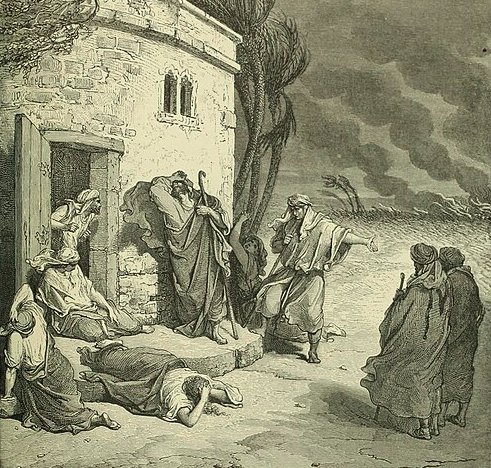

It's very hard to do justice to the Book of Job. It's one of the most challenging, most thought-provoking works of theology ever written; for more than two millennia, it has been a source of intrigue, insight, outrage, and bewilderment to its readers. For those unaware, the Book of Job describes the suffering of a righteous man, whose family, possessions, and health are taken from him by a divine adversary (Hebrew hassatan, "the accuser", from which we get the proper name "Satan"). This is only possible because God has allowed it in response to Satan's challenge: Job only worships God because he's rich, healthy, and secure. Job's friends, after having mourned with him for seven days, begin to pry into the possible reasons for Job's suffering, and that goes about as well with Job as you would expect. Time after time they insist that Job must have done something to deserve it, and time after time Job protests his innocence. Then, at the very end of the book, Job receives a theophany- a direct revelation of God- which for many readers raises more questions than it answers. It is a hard, complicated, beautiful book.

The consistent theme of the questions I hear asked about the Book of Job is something like this: "isn't it unfair for God to let the devil torture Job? Doesn't it all seem a little unnecessary? Couldn't God just have let the Devil run his mouth for a bit and then send him on his way, leaving Job as he was?" It's a pressing concern. He is God, after all. He's not beholden to the opinions of lesser beings. Does He really need to let Job suffer so harshly just to prove a point? There are some people, reasoning along these lines, who hold up the book as proof that God is unjust- perhaps even evil. This is a claim I intend to take very seriously. If God is not justified in causing Job to suffer, then Christian theology needs some major revisions. I am not sure any revisions will ultimately be necessary, but I thought it would be good to get an idea of the stakes.

This will be the first of a series of posts on this subject. The Book of Job is complex and multifaceted, and we tend to complicate our own reading of it with misapprehensions about what is actually happening in the text. My objective is to examine some of these and to challenge them, starting with what I believe to be the main one.

God does not play dice

If you have already heard about the book of Job, it has probably been described to you as the book where God makes a bet with the Devil over the soul of an innocent man. This tends to make people indignant. "How can God do that? How unfair! I would never do such a thing if I were Him!" Rightly so- I wouldn't, either. It is bad enough to gamble with your own money, worse still to gamble with someone else's money, and unthinkable to gamble with someone else's soul. God is supposed to love us, is He not? All that talk in the Psalms about his care for the poor and the downtrodden- yet here He is, treading Job down and impoverishing him of everything he holds dear.

In my experience, it is this view of things which forms the lynchpin of most critiques of the Book of Job. God is understood to be aloof and callous and uncaring. He is content to trample on us mere mortals, provided it furnishes Him with an excuse for extolling His own greatness. Job is just a helpless, clueless casualty in a battle he didn't know was being fought. He is an insect crushed by a tank-tread. This dynamic is expressed most clearly in the wager between God and Satan, in which the latter is invited to ruin an innocent man's life while the former watches carefully to see if he will desert his faith.

The trouble with this version of events is that it is largely fictional. I invite everyone to read the dialogue between God and Satan closely:

6 - Now there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the LORD, and Satan also came among them.

7 - The LORD said to Satan, “From where have you come?” Satan answered the LORD and said, “From going to and fro on the earth, and from walking up and down on it.”

8 - And the LORD said to Satan, “Have you considered my servant Job, that there is none like him on the earth, a blameless and upright man, who fears God and turns away from evil?”

9 - Then Satan answered the LORD and said, “Does Job fear God for no reason?

10 - Have you not put a hedge around him and his house and all that he has, on every side? You have blessed the work of his hands, and his possessions have increased in the land.

11 - But stretch out your hand and touch all that he has, and he will curse you to your face.”

12 - And the LORD said to Satan, “Behold, all that he has is in your hand. Only against him do not stretch out your hand.” So Satan went out from the presence of the LORD.

Job 1:6-12

With that in mind: where is the wager?

The typical response would be something like this: "well, clearly it's in verse 12, where God gives Job's family and possessions over to Satan. He's betting that the Devil can't turn Job against Him." But look again. Where exactly is this bet being made? A careful exegesis of the passage turns up no reference to it, explicit or implicit. All we have is Satan making an ominous proclamation that Job's faith in God will not survive tragedy; if we want to read God's response as a bet, we would have to assume that God doesn't know whether the Devil is wrong. Not only would that be an eisegetical reading, it would also raise a theological red flag. God does not need to wait for the outcome of a bet to know whether or not Job's faith is strong enough. The Book of Job itself is replete with references to God's omniscience:

He gives them security, and they are supported, and his eyes are upon their ways.

Job 24:23

For he looks to the ends of the earth and sees everything under the heavens.

Job 28:24

Does not he see my ways and number all my steps?

Job 31:4

For his eyes are on the ways of a man, and he sees all his steps.

Job 34:21

Job's entire plea for the rest of the book rests on the repeated insistence that God, who sees all, knows he is a righteous man, even if his friends don't (and, as we will see later in this series, he was right to make this appeal). Unless we are to take the text as directly contradicting itself, then we have to read this passage with the understanding that God is all-seeing and all-knowing. That makes it impossible to argue that God is gambling with the devil. One can only gamble if the outcome is in doubt, but from the divine perspective, no outcome is in ever doubt.

Time and again, it's this false notion of a wager which trips people up. It does not exist; God never concedes the possibility that the Devil might be right. The notion that God has agreed to some kind of wager exists entirely in our own heads. We are reading this into the text; a clear exegesis of the passage does not support it. When God withdraws His protection from Job, it isn't because He felt the need to up the cosmic stakes by putting Job's life on the table. I appreciate that I'm hammering this point, but it needs to be driven home. People are attacking God's conduct on the grounds of something that the text doesn't say- not only that, but something which the text precludes as a possibility.

But do you take the Bible literally?

I think that the driving force behind this misapprehension is the picture that comes into our heads when we read Job 1 and 2. These chapters describe divine realities in very prosaic terms. God feels the need to ask Satan where he's been, and then immediately launches into a speech about his righteous servant, Job. If, as I read this passage, I reflect on the kind of scene it creates in my mind, I find something almost cartoonish. God, sat on a throne up in the clouds, making booming and unprompted proclamations at the Devil, seemingly oblivious to the fact that He is being goaded. It tempts me to take the passage lightly, to take a view of God which doesn't quite do justice to the subject matter. I don't think this is rare; I would venture a guess that most people who criticise the Book of Job have in their minds some variant of this picture.

The obvious problem with this is that it can't possibly be correct. If we are to entertain the possibility of a divine realm beyond the material world (as this book invites us to) then surely it must transcend the ability of the human mind to comprehend it. There is that infamous question: "do you take the Bible literally?" I don't like this question. I think that it's a mess of mixed concepts masquerading as something which requires only a simple yes-or-no answer. This particular topic- the attempt to describe divine realities- is a good place to start in unravelling that question. Of course I don't believe that God and Satan spoke Biblical Hebrew at each other; I find it very hard to imagine that the author of Job was listening at the door to the divine throne room and jotting down notes. If that is what you mean by "literal", then I can't affirm it, and I don't think the author would have affirmed it either.

The ancients were not stupid. If you were to press the author on whether he really believed that God and Satan spoke these exact words to each other, like two people holding conversation, I imagine he would have given you a strange look. Naturally no mere mortal would be able to describe divine realities as they really are (for a good example of this, read Ezekiel). The language of the Book of Job cannot help but evoke pictures which are too simplistic; it couldn't possibly do justice to the events it purports to describe. I have to assume that God's interactions with the Devil involved means of communication which have no direct physical correlate; the book renders it as human speech because that's the closest analogue.

If we keep all this close to the front of our minds when we read the Bible, it will act as a counterweight to our imagination, should we ever find ourselves imagining too shallow a version of things. It will also safeguard us against the kind of chronological snobbery (see resources below) which runs rampant in these discussions. Ancient writers knew far less about science than we do; but that has far less relevance than we tend to assume, and in this particular discussion it has no relevance at all. They were quite well aware than pen and papyrus would never be able to capture the full weight of divine reality.

Fording the river

To bring it back to the central point: I think that, in part, we object to God's treatment of Job because right from the get-go we are labouring under a misapprehension. We read God as responding to the Devil's challenge as we would respond: "alright then- prove it." This is fostered by the pictures of the scene which we imagine; though we don't do it intentionally, these pictures are never accurate, and don't come close to capturing the profundity of what the text is trying to describe. More often than not, they get in the way.

There is an antidote to this, however: if the text is what it purports to be, then there is a reality behind the text which far transcends it. The text, far from inventing a fable, is distilling this greater reality into a form which we can understand. I am not asking the reader to accept the existence of this reality; all I am trying to do is put the issue into context. Naturally, if this reality does not exist, then the whole question of God's justice is irrelevant, and there is no point going any further in our consideration of the matter, whether the text tells us about a wager or not. But I think it would be too hasty to say this.

Now, the question which all this raises is immediately obvious: if there is no wager, and what happens to Job is not some arbitrary test of faith, then why on Earth did it happen? What could compel God to let the Devil torture a good man? The answer to that question isn't as obvious. Indeed, there may be more than one answer, and all of them will have to reckon with the problem I outlined above; that human language can only ever approximate the things of God, and never fully capture them. But that is for another post.

For further consideration

One of the most useful concepts you will ever learn about: Wikipedia | Chronological snobbery

C. S. Lewis on the above: C. S. Lewis Institute

All Bible citations are from the English Standard Version unless specified otherwise.